Michigan HistoryThe Detroit News in Antarctica This photo of Lake Bonney in Antarctica was taken by Detroit News science writer Jean Pearson as she accom- panied a science expedition in 1969-70. By Vivian Baulch / The Detroit News September 19, 1999 Rear Adm. David F. Welch, commander of the U.S. Navy task force which supported the National Science Foundation's research program at the South Pole, ruled that newsmen with cameras would get off the plane first in order to record arrival of the women scientists.

Thus Pearson, by virtue of her "newsman with camera" designation, became the first woman to step foot on Antarctica. Men first visited the continent in 1912 when Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen beat British naval captain Robert Falcon Scott to the South Pole by almost a month. The next men to reach the pole, Rear Adm. George J. Dufek of the U.S. Navy and his crew, landed an LC-47 at the pole Oct. 31, 1956, as part of a scouting expedition for the next year's International Geophysical Year. They established the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station where the highest temperature is about 5 degrees. Winter and summer become two long days and nights, each lasting six months. It took the science team and the Navy six months to prepare for "Operation Deepfreeze." The Navy had little experience operating under such extreme conditions. "If it weren't for the science program, we wouldn't be here," said Adm. Welch. "All cold weather clothing necessary for comfortable existence will be issued you at the supply stop at Christchurch, New Zealand," participants in the mission were told. "Don't bring anything more than you can carry yourself -- because you'll be the one carrying it." After arriving in New Zealand with two bulky cameras hanging from her neck, Pearson, and the others reported to the Navy's "Penguin Airlines," a C-131 Hercules cargo transport dubbed "the World's Most Experienced--and Only--Antarctic Airline." Its wheels barely showed below the skis. Inside bare-metal seats bolted down amid lashed cargo greeted the passengers for the eight hour trip to McMurdo Station in the Antarctic, where the team was put up in rows of huts dubbed the Ross Hilton. Pearson wrote a series of articles in The News that appeared Jan. 27 through Feb. 6, 1970. She also brought back many photographs. In one story she she told of her experience studying seals: "So there I was, lying stomach flat on the Antarctic ice, eyeball to eyeball with a 900 pound female Weddell seal," she wrote. "Snuggled next to her was a young pup with round, wide-open, innocent eyes and an upward curving smile. He probably weighed about 80 pounds.

"Just as I was ready to shoot she decided I was indeed an uninteresting specimen of land life and started to drop her head to laze a bit more in the sun. Trying to regain her attention, I flipped my glove up and down. 'So who cares?' she snorted. Then I gently flicked the whiskers of her pup. 'Ah, Oh Wow!!' she bellowed, the whole inside of her pink mouth showing." The team studied the Ross, leopard, crabeater and Weddell seals, all protected from fur hunters by an international agreement. In another article Pearson described encounters with penguins. "To penguins, people are apparently penguins. At least they let people wander through their rookeries without flapping a black flipper. But if you try to steal a prized pebble from their little round nests of stones, you'd probably get lunging pecks by a hard, feathered beak and some vicious swats from sturdy flippers. That's what happens to penguins who steal pebbles." About 18 inches high the Adelie weighs about 14 pounds, cannot fly and treks about 50 miles across ice to its rookeries. The larger Emperor penguin stands about three feet high, weighs 70 pounds, wears a necklace of golden feathers, and carries its baby on its feet for about two months. "The mate of the penguin I'd chosen to photograph sitting on her pebble nest (being careful not to kneel in the slimy green guano) wasn't in evidence," Pearson wrote. "But just as I was moving in for a close-up, I caught sight of him, waddling rapidly toward the nest with a pebble treasure in his beak. He approached very politely, and waited while I focused on the love of his life.

"I tried several exposures. When I finished and stepped away, he resumed his waddling trot and dropped the pebble at his mate's feet."

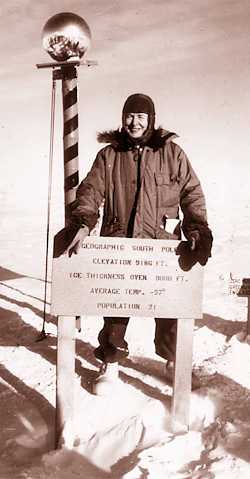

But before the group was made it to their research site, they were put on the list of Pole tourists, with much media hype...at the time there were 7 women on the ice. This included the four members of Lois' team, Christine Müller-Schwarze who was studying penguins at Cape Crozier, Pam Young, a NZ biologist, and Jean Pearson, then a reporter for the Detroit Free Press. Christine declined the trip because it would interrupt her research, but the other 6 women headed south on an LC-130 on 12 November 1969. Their arms linked together, they stepped off the ramp simultaneously...walked around the Pole, posed for pictures, and flew back to McM, where they eventually ended up at their field sites. The scientists also studied the ice and the water. Their first project was hand-drilling through 14 feet of ice to reach the water of Lake Bonney. What the women scientists feared most was having the auger freeze up. This often happened to the men as they drilled, but the women knew they would never live down the same bit of bad luck. After three and a half hours of steady drilling, a hollow, slushy sound proclaimed that the water had been reached. By then it was quitting time. The next day the hole had completely frozen over. Antarctica, a continent larger than the United States and Mexico combined, was first sighted by modern man in the early 1800s. The world's stormiest seas had long protected the mountains and the icy interior from discovery and exploration. Scientists had speculated that Antarctica long ago was part of a hugh tropical supercontinent called Gondwanaland, named after a province in India. They hoped to find fossil evidence that would support the theory. During the 1969 expedition a team of fossil experts, Dr. Edwin H Colbert, Dr. Paul Tasch and Dr David H. Elliot came to look for old bones. In November they found the bones of a theodont, an ancestor of alligators and crocodiles. In December Dr. Colbert found the reptilian skull of a Lystrosaurus, a two- to four-foot long hippo-like freshwater reptile. "Lystrosaurs had a peculiarly shaped skull, with the nostrils high on the skull between the elevated eyes. This most surely indicates aquatic habits" he wrote. In a later report the scientists wrote: "The presence of fresh-water amphibians and land-living reptiles in Antarctica some 200 million years ago is very strong evidence of the probability of continental drift because these amphibians and reptiles, closely related to back-boned animals of the same age on other continents, could not have migrated between continental areas across oceanic barriers." If the continental drift theory is valid, the scientists said in their report, "Antarctica was once part of a great southern land mass known as Gondwanaland."  Pearson, center, with other members of the expedition. (This story was compiled using clip and photo files of the Detroit News.) [The originally formatted story is no longer online.] |