Max Conrad at Pole....continued

|

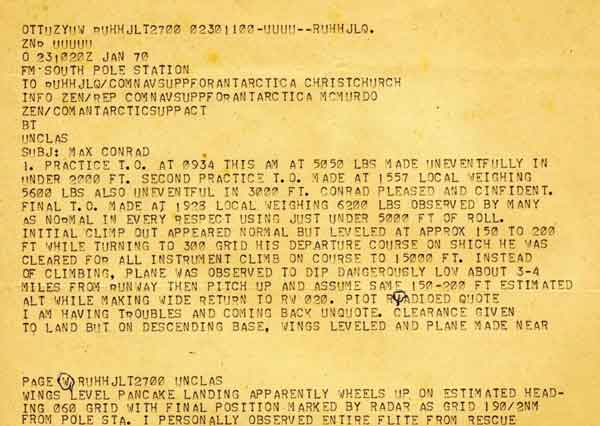

Then it was time to head off for Punta Arenas. 23 January. Although the route plan on the postcard included a stop at Byrd, this would have required the skis, which Max had brought along but did not want to use. The preliminaries involved not one but multiple takeoffs, one of which is seen above (all photos on this page are from Bob Little (BL) unless indicated otherwise). Conrad was practicing takeoffs with increasing fuel loads to see how much weight he could get away with for the long flight to South America, and at the same time experimenting with radar and his compass, which he'd need to rely upon for most of the trip. What happened next is best described in Max's words in a letter he wrote at Pole after the crash: "Well, we did not make it, but N123LF was the first civilian aircraft to land at the South Pole. Furthermore, N123LF made 3 takeoffs from the skiway at the pole, 1) weighing 5000 lbs. on wheels in 2500 ft. 2) weighing 5700 lbs. in less than 3500 ft., and 3) weighing 6400 lbs +/- in 5500 ft. Piper can be proud of that kind of performance." The test flights were interrupted by ice fog, which later cleared away and left blue sky. Afterward, Max received word from the weather folks in McMurdo that flight conditions would be good if he left that evening. So he did. But the local ice fog had returned, making visibility poor. This low cloud cover can produce a whiteout condition in which one can't tell the difference between the sky and the snow surface. Max climbed out to 500' above the snow surface, but when he went to bank left and head for the Peninsula, he was closer to the snow that he thought. He tried to pull up, but his left propeller struck the snow surface. This of course caused severe vibration which threatened loss of control. He tried to turn and get back to the skiway, but instead he went across it. He then tried to bank right to avoid the antenna towers which he knew were ahead, but he ran out of altitude. At some point he caught the left wing tip, shearing off the fuel tank. He then crash landed, wheels up, full power, and actually with relatively little visible damage. And no injury to the pilot. A few photos of the aircraft the day after the crash: | |

|

The aircraft was not repairable; according to Max it would have required two new engines and propellers as well as a wing, as is obvious from the two photos below (from Bob Hutt). Max stayed around for a few days to deal with the rest of his philatelic postcards. He also had to cover the aircraft to protect it from the elements, and remove all of the electronic gear that he could, for insurance purposes. He left Pole (in a VXE-6 LC-130) on 30 January. The two photos below are from Bob Hutt (BH). | |

|

A couple of pictures of the aircraft after the winter, on 26 October: |

|

|

Max did not try again. He went back to being a ferry pilot and went for a few more long-distance flight records. He died in 1979; the airport in his home town of Winona, Minnesota was named for him. The story at Pole was not quite over; the aircraft had crashed about a mile from the station alongside the skiway, where it gradually became buried as seen above. During the 1971-72 summer it was dug up and moved close to the station, where Ron May, one of the Navy GCA crew, had his picture taken in what was left of the White Penguin (RM).  Later in the summer the aircraft was reburied at the end of the original station skiway, where presumably it is today. A side note on what might have happened--Walter Pederson showed up in Christchurch in January 1971 in a C-121 Super Constellation and a load of snowmobiles in an effort to recover Max's aircraft. The Pederson Expedition is another story... Information references and sources (with thanks):

[NOTE: any other additions, photos, corrections or credits would be welcome --Bill (email)] | |