U.S. airplane recovered from East Antarctica

[from the Antarctic Journal (NSF), March/June 1987] [all issues are available here]|

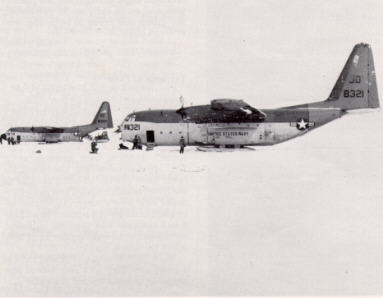

On 25 December 1986, Juliet Delta "321," a ski-equipped Lockheed Hercules airplane, sat on the snow surface at an isolated site in East Antarctica (68°20'5 137°31'E), 190 kilometers from the Background In this region of Antarctica, high-speed, gravity-driven winds (katabatic winds) create ridges (called sastrugi) in the snow surfaces. Because of this rough, broken snow surface, the 1971 aircrew decided that a jet-assisted takeoff (JATO), which uses small solid-fuel rockets to boost the airplane's turboprop engines, was necessary. Seconds after the airplane took off, two of the 165-pound JATO bottles broke loose from their attachment points on the left rear fuselage, struck the number 2 engine, and destroyed its propeller and gear; flying metal fragments damaged the number 1 engine. Although the pilot brought the airplane, which was only 15 meters above the ground, with its 10-man crew safely to the ground, the emergency stop on the rough surface collapsed the nose landing gear. The LC-130 that arrived 4 days after the accident to rescue the crew brought a Navy accident-investigation team. The team's evaluation was that the extensive damage and remoteness of the site made recovery impossible, The airplane was abandoned after being stripped of instruments and other equipment that could be easily salvaged. The crash site, called D-59, is along a traverse route frequently traveled by Expeditions Polaires Francaises personnel, and during the next decade French traverse parties visited "321" almost every year. They noted annual snow accumulation around the airplane and more than once provided the U.S. program with surveys of the site. During the 1975-1976 and 1976-1977 austral summers, two U.S. LC-130s that crashed at Dome C (an isolated east-Antarctic site near D-59) were recovered successfully. These successes renewed interest in recovering "321," In 1978, four engineers examined the damaged airplane at D-59 (now covered by approximately 1 meter of snow), determined that the damage was less than originally thought, and recommended recovery. Recovery was planned for the 1979-1980 austral summer, but budget restrictions and other problems forced program managers to cancel the project. No future plans were made until June 1986 when the National Science Foundation announced its intent to recover the airplane, if still possible. Recovery plans Before the 1986 announcement, staff members of NSF's Division of Polar Programs (DPP) began collecting data on the status of the airplane and the conditions of the site. In December 1985 a French traverse party, which included an American, Rob Flint, visited D-59 and gathered information about the airplane. Observations by the French traverse party, along with Mr. Flint's report, were supplemented by the reports that VXE-6 crew members made after two attempted landings of LC-130s at D-59 during late 1985. This information confirmed that before an LC-130 could land safely at the site, an adequate skiway would have to be prepared. In addition, DPP learned from these reports that "321" was almost completely buried. Only the top 1.5 to 2.0 meters of the airplane's tail, which juts 11 meters into the air, was still above the snow. No more detailed information could be obtained until excavation efforts began. Despite these reports, interest in salvaging the airplane continued at NSF. In April 1986, ITT/Antarctic Services, Inc. (ITT/ANS) submitted a recovery plan to NSF. The plan was reviewed, revised, and later discussed at a U.S. Antarctic Program logistics and support meeting in Port Hueneme, California. Once all of the program participants (NSF, NSFA, VXE-6, and ANS) had studied the plan and NSF had approved it, the ITT/ANS project manager James Mathews began recruiting the five people needed to complete the project. Throughout the 1986 summer, Mathews and the ITT/ANS team worked closely with the commanding officer of VXE-6, Commander Joseph Mazza, and with VXE-6 aircrews and maintenance personnel. They inspected and photographed an LC-130 at the squadron's base in Point Mugu, California. They studied and discussed the workings of the LC-130 ski/wheel landing gear with VXE-6 maintenance personnel. During a meeting in Port Hueneme, Roger Biery, the ITT/ANS heavy-equipment operator, identified special attachments that would be needed for the heavy equipment selected for the project. After researching potentially useful parts, two special lightweight, high-capacity buckets were ordered for the selected tractors and tracked vehicles. These attachments would improve snow-moving capabilities by 30 percent or more. A cold-weather cab for the one of the tractors, which would be required at the job site, also was purchased. Following the schedule developed during the planning meetings, Roger Biery and Russ Magsig, heavy equipment mechanic for the project, went to Antarctica in late August 1986 to prepare the heavy equipment and other supplies. While Biery and Magsig worked in Antarctica, George Cameron, the project engineer, and James Mathews visited the Lockheed Georgia plant in Marietta, Georgia, to discuss plans with two Lockheed engineers, who had participated in the recovery work at Dome C in the 1970s. By mid-September 1986, Mathews had developed a plan to deliver supplies and equipment in a sequential and timely manner. NSF, NSFA, and VXE-6 reviewed the plan at a meeting held during the U.S. Antarctic Program's annual orientation conference in Washington, D.C. The plan was approved, and final preparation for the project began.

Preparation in Antarctica McMurdo Station.J. Mathews, G. Cameron, and M. Brashears (cook/medic/ radio operator and weather observer) joined Magsig and Biery at McMurdo Station in early October, D, Check, the second heavy-equipment operator and final member of the crew, arrived in early November. Because Magsig and Biery had prepared all of the heavy equipment for the project, the only equipment-related tasks remaining were to verify that the blades, bucket, and cab fit the equipment and to dismantle two tractors for shipment to D-21 or D-59. To shelter the team while they worked at D-59, Mathews designed a special living module (see sidebar). After the materials needed for the module were inspected, ITT/ANS personnel began to build it, white R. Biery constructed a ski cradle for it. When the basic structure was complete, the module was moved to the sea-ice runway near the station to be furnished and tested before shipment. The Expeditions Polaires Francaises Traverse Party, headed by Pierre Laffont, arrived at McMurdo Station during the last week of October. At the request of Mathews, they inspected the module and verified that it could be towed successfully to D-59 from D-21. With this confirmation, Mathews immediately added the module and some Jamesway components to list of equipment to be transported to D-21. By doing this, he hoped to make the team as self-sufficient as possible when they arrived at D-59 and to minimize the impact of delayed flights to the site because of bad weather or airplane maintenance problems. On 2 November 1986, all essential cargo for the project had been prepared for shipment and stationed at the sea-ice run- way. D-21. On 3 November 1986, R. Biery, R. Magsig, and J. Mathews, along with the French traverse team, departed for D-21, the landing area 22 kilometers inland from the French station Dumont d'Urville. A second airplane, carrying skiway construction equipment, followed. Wintering personnel from Dumont d'Urville had prepared a rudimentary skiway for the first two flights. As soon as the ANS crew received their equipment, they began to improve skiway landing surface so that an LC-130 carrying 135,000 pounds of cargo and fuel could land. With this task completed the team was ready for the next flight on the morning of 5 November 1986. Bad weather near McMurdo Station and at D-21 delayed many flights during the next 2 weeks. Because these storms were severe, the team was forced to reconstruct the D-21 skiway completely after the last storm had dissipated on 18 November. Nevertheless, after the eighth and final flight brought the last passengers and cargo early on 19 November, the group was ready to begin the traverse to D-59. Traverse to D-59 Expeditions Polaires Francaises traverses are well established and highly organized, The 220-kilometer overland traverse to D-59 involved navigating between metal poles, spaced 10 kilometers apart from a location known as "Carrefour" (D-40) to their terminus at D-120, approximately 800 kilometers inland. Each season, detailed records of the traverse are compiled and passed on to the next year's party. Navigation instruments vary but traditionally include a sun compass and azimuth indicator; consequently, traverse parties travel only when the sun is visible. The terrain between D-21 and D-59 is a series of rolling hills and valleys that gradually ascend toward the polar plateau. Snow accumulation is low with some areas receiving no snow at all, and katabatic winds create remarkable sastrugi patterns. Near D-59 winds and precipitation annually change the terrain. In 1986 as the group approached the site, they encountered sastrugi that ranged from 11.2 to 1.5 meters high. To compensate for the time lost at D-21, they traveled at least 12 hours each day. About 1 kilometer ahead, the French navigation vehicle led the tractor train, which was led by one of the U.S. vehicles, a low-ground pressure D-6 bulldozer pulling two 10-ton sleds. The bulldozer improved conditions for the rest because it had sufficient power to raze a road, On 23 November, less than 4 days after leaving D-21, the party reached D-59. At the crash site, they found that only the top 1 meter or so of the vertical stabilizer was visible--an incongruous feature rising from an otherwise featureless horizon. D-59: Camp site and excavation work After selecting a camp site the next day, the group prepared for a scheduled air drop of 7,500 liters of diesel fuel (DFA) and 2,200 liters of gas (MOGAS). The air drop went well; only eight drums of DFA were lost when two parachutes did not open. With this fuel shipment the project team could be self-sufficient for at least 2 weeks, and work could continue if the scheduled supply frights from McMurdo were delayed. The skiway was completed on 27 November in time for the second supply fright. Arriving the next day with additional diesel fuel, this airplane was the first to land at D-59 since January 1978. Over the next 2 days, three more LC-130s brought supplies and equipment. By 1 December, all the equipment needed for the project had been delivered, and only fuel frights scheduled for late December remained. The French team began its return trip to D-10, although radio operator Didier Simon stayed with the U.S. team for the season to observe and to assist with snow shoveling.

Weather at D-59. In December the weather at D-59 is generally windy. Although during the first week a 3-day storm did interrupt work, throughout the project the winds did not prohibit a full day of tractor or other outside work. The skies were frequently clear or had only scattered clouds; the average wind speed was moderate (8-20 knots). Even days when the wind exceeded 20 knots were acceptable for working, as long as no snow had fallen recently. Fortunately, from 5 to 25 December, when most of the excavation and the towing work took place, the good weather was almost uninterrupted. Although extended good weather at D-59 may not be common, the team generally believed that the weather during December is probably similar to other areas of the continent's interior at this time of year. From 10 to 20 January 1987, a series of marine weather systems (like those prevalent at Siple Station) occurred and combined, in its last stages, with sustained katabatic winds. If this storm had occurred when the airplane was still in the excavation pit, the team would have needed at least an additional week's work.

Excavation. Experimental excavation around "321" started on 26 November, but not until 30 November, after a tracked caterpillar loader with blade and bucket was received and assembled, did the team seriously begin removing the snow around the airplane. The team first tested digging methods to find a way to prevent further damage to the airplane, They selected an area near the number 1 engine, which had been damaged in the crash. During this early stage of digging, they discovered that "321" was covered by 6.0 to 7,5 meters of snow rather than the presumed 3.1 to 4.6 meters, Also, once digging reached the 3-meter level, they found dense, compact snow with melt ice near many of the airplane's surfaces. For a week, they worked to uncover all of the top surfaces and to open the way into the airplane. While digging they observed that the airplane would rise noticeably when large amounts of snow were removed. This observation suggested that snow-loading over the entire structure was significant but uniformly distributed and probably had not damaged the airplane's structure. To prevent damage to the structure, they decided to remove the snow from the center wing sections and forward fuselage last. On 10 December they entered the airplane for the first time. They found the fuselage intact with some damage to two escape hatches and some cracked windows on the flight deck. During the week that followed, excavation work moved rapidly. With all of the top surfaces free of snow, they began to build the ramp on which they would tow the airplane out of the excavation ditch. To construct this ramp, they had to trench backwards from the 10 meter snow wall in front of the airplane. When it was completed 1 week later, the ramp was 100 meters long with an angle of 330. On 16 December, working 7.5 to 10.0 meters below the surface, they began to uncover the fuselage and to remove the snow from between the engines. Snow that was dense at 3 meters or so was extremely hard at this level. To make removal easier, the crew used one of the tractors to move the snow and a chain saw to remove snow inaccessible to the tractor, As pressure was released, the airplane rose more; consequently, the amount of hand shoveling needed to free the airplane's structure was reduced. The entire airplane rose an average of 5 to 7 centimeters but the most dramatic rise occurred when the left outer wing tip rose approximately 80 centimeters Over 5 to 6 days. On Christmas Day 1986 after an unsuccessful first try, the ANS crew towed Juliet Delta "321" out of the snow pit and onto the surface at D-59. They cleaned the interior and prepared the plane to be reviewed by experts from the U.S. Navy and Lockheed Corporation.

Its engines were removed in early January 1987 by a five-person maintenance team from VXE-6. The four engines and three propellers were returned to McMurdo and later to the United States for repair. Salvage of the engines and propellers alone paid for the cost of the entire project many times over. The aircraft has been examined by structural and electrical engineers from Lockheed and the Naval Air Rework Facility in Cherry Point, North Carolina. Based on their preliminary findings, their assessment is optimistic that "321" can be rehabilitated and flown from the site. The D-59 camp was closed on 21 January 1987 with "321" parked 100 meters down wind of he camp. During the 1987-1988 austral summer only 2 to 3 days of excavation should be required to remove accumulated snow from around it. All equipment and supplies were consolidated and inventoried for easy access when the camp is reopened. Everything required for immediate start-up and skiway construction was left behind, including enough DFA for at least 1 month of operation. Conclusion For almost 15 years this project was considered to be too costly, logistically complex, and dangerous to be practical. As the years passed and "321" disappeared from view, recovery attempt was thought to be hopelessly uncertain. Ultimately, many people considered it to be impossible. Its recovery is credit to the human resources of the U.S. Antarctic Program. That this effort was accomplished ahead of schedule, with minimal disruption to the U.S. Antarctic science program, and at a reasonable cost is a credit not only to the people who did the work, but also to those who sponsored and coordinated the recovery. When "321" flies again, it will be because of the combined efforts of personnel from ITT/Antarctic Services, the Naval Support Force Antarctica, Antarctic Development Squadron Six, and the National Science Foundation's Division of Polar Programs. (Editor's note: This article is based on the final project report written by James C. Mathews, project manager for the "321" recovery.) |